By mid-November of 1963, the theme for the next big Los Altos High School dance had been established. The theme was going to have something to do with the sea; boats, underwater critters, fishing nets, etc. As lowly sophomores who probably wouldn’t get dates for the dance anyway, my friends and I took it upon ourselves to help provide decorations and some kind of coastal ambience. The plan was to drive over to the coast and steal a city limits sign from one of the quiet hamlets south of Half Moon Bay. The sign would end up in the high school gym as appropriate decor for the dance and we would be regaled for our resourcefulness.

By mid-November of 1963, the theme for the next big Los Altos High School dance had been established. The theme was going to have something to do with the sea; boats, underwater critters, fishing nets, etc. As lowly sophomores who probably wouldn’t get dates for the dance anyway, my friends and I took it upon ourselves to help provide decorations and some kind of coastal ambience. The plan was to drive over to the coast and steal a city limits sign from one of the quiet hamlets south of Half Moon Bay. The sign would end up in the high school gym as appropriate decor for the dance and we would be regaled for our resourcefulness.On November 21, two days before the dance, we put our plan into motion. Four of us squeezed into Stan’s little Volkswagen bug and, late in the afternoon we headed over the winding, narrow road west of Crystal Springs Reservoir, up and over Skyline Boulevard, and down the curvy backside of the coast range past flower farms and nurseries to Half Moon Bay. From there it was a relatively straight shot south on Highway 1 to the town of Pescadero.

Pescadero had a special meaning for us because we liked to spend time poking around its rocky coastline and enjoying the maritime atmosphere. And, of course, the name was colorful and very coastal Californian. In any case, we reached the outskirts of Pescadero near sunset where we found the simple, green and white metal sign bearing the town’s name. Back in those days, it was fairly easy to make off with street signs like this one, attached to a pole as it were with only two bolts. With a handy wrench we made quick work of the hardware and, while one of us stood guard to make sure no traffic was in sight, the sign was removed and furtively thrown into the back seat of the bug.

You can probably guess the rest of this little story. The following day was November 22, 1963. I was at home that morning faking a head cold and watching television when the defining event of my generation occurred....the assassination of JFK. Needless to say, the big dance was cancelled. The Pescadero sign stood unused in my parents’ garage thereafter.

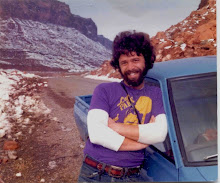

In subsequent years that sign moved with me and was often displayed in various parts of the American West....in the canyon country of Utah, at Point Reyes National Seashore, in backyards in Phoenix, Redding and Albuquerque, and many other locations my transient existence took me. And I still have it.

Last summer when I chanced to drive through Pescadero once again, I found it was as sleepy and bucolic as it had been back in the 1960s. The new city limits sign was much smaller and much more securely fastened to its post. And I found myself thinking that some day I would like to return to Pescadero, approach the city fathers (if there are any) with my story, seek forgiveness, and return the sign. It has been a part of my life now for nearly 50 years, so maybe it is time to take it back home.