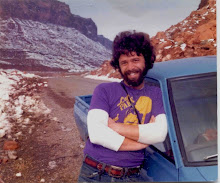

My first day on the job in Canyonlands,

I was confronted by Harry Yount, first-ever park ranger and mountain man of

Yellowstone, whose leathery countenance stared out at me from a faded

photograph in the dilapidated trailer we called an office in the Needles

District – the very same trailer, I was told, in which Ed Abbey wrote Desert

Solitaire when he was a seasonal ranger at the Arches. Over the next few weeks, I’d hear this

particular rumor applied to several other weathered metal hulks scattered

throughout the canyon country,

My first assignment in the Needles:

Learn how to drive a jeep, and head up to Davis Canyon to repair a vandalized

cliff dwelling. I was introduced to Ken,

a fellow ranger and native of Moab, Utah.

Within minutes of our meeting, we were in a lime-green government rig,

moving quickly under a cool gray sky.

About five miles from headquarters we took

the turnoff to Davis Canyon, leaving the paved road and the broad valley of

Indian Creek for the avenue of cliffs beyond.

I absorbed as much of the scenery as possible while Ken drove the first

part of the canyon, offering tips on vehicle control and pointing out

ruins. I settled into the bouncing

rhythm of the jeep and began training my eyes to see the subtle signs of prehistoric

habitation – little square windows against a cliff, methodical layers of

sandstone masonry.

Shortly past noon we reached our

destination, a narrow drainage filled with Indian ruins on both sides. The one we were looking for was perched on a

ledge under a pothole arch and we’d have to climb down to it from above

The air grew chill and dark, biting

against our faces as we climbed the rounded cliffs of sandstone. We were soon on top, moving carefully across

ledges, carrying rope and climbing gear over our shoulders, stopping finally at

a large horizontal hole in the cliff twenty feet across and shaped like an

immense toilet seat.

We walked around the far side of the

hole until we could see below us a narrow ledge about fifteen feet away. Perched upon it was a small square structure

of earth and stone. A nearby juniper

provided a belay point for our ropes as we tied them off and rappelled down to

the ledge. The ruin was about five feet

thigh, its ceiling built squarely against a curving wall of the arch. A wooden floor divided it in half, and there

was a small opening in each level. I

marveled at the workmanship, at the ancient fingerprints still visible in the

dry mortar. It was a two-story granary

of some kind.

A small dried up corn cob lay nearby,

its shape barely altered by time. While

it looked like it might have been discarded only recently, we knew we were

looking at an agricultural product from 700 years before, preserved intact by

the dry climate. We began looking for signs of vandalism. The granary was in excellent shape, probably

visited by only a handful of people a year.

But around its backside, nearly hidden in the shadow of a nearby wall,

someone had carved their message in the ancient clay, in letters almost an inch

high:

HA-HA. WE WERE HERE BEFORE YOU.

As the sky darkened through the oval

opening above us, I could almost feel the presence of Anasazi spirits

condemning the modern intruders. I turned to Ken and suggested we wet some of

the fine red dirt, make a paste out of it, and plaster it over the

letters. We mixed our saliva with the

dust, making clay in our palms and applying it to the graffiti. The letters disappeared as the clay blended

in, and the wall’s original appearance was restored. As we paused to admire our work, we hear the

sound of rain up above.

“Jeez, we’d better get out of here fast

before the rock gets too slick! Do you

know how to use jumars?” Ken asked.

“It’s been a while, but I think so.”

Actually, I sucked at using jumars but I didn’t want to admit it.

We quickly attached the jumar handles

to the dangling rope, their looped ends going around my boots. I began my ascent, slowly lifting each handle

and each leg in unison as the rain increased in intensity. It was slow going as the rope became damp and

slippery. I was nearly halfway to the

top when I saw a small trickle of water spilling over the same notch where the

rope hung. Soon it was splashing my face

and running over my hands. Despite

mounting anxiety, I managed to reach the top.

I immediately dropped the jumars down to Ken. By this time, a small stream was flowing over

the lip of the arch, pouring right onto Ken who was struggling with the

equipment, trying to slide each jumar up the saturated rope.

When he neared the top, I grabbed the

rope and pulled with all my strength until Ken made it over the lip and onto

relatively level ground. We swiftly

gathered our gear and headed over the rocks toward the jeep, the rain now a

relentless torrent, unleashing waterfalls and sudden streamlets from every

direction, as if someone had turned on hundreds of faucets all at once. Slipping several times as we ran, ropes

dangling, packs bouncing, we soon saw the jeep just a few hundred yards

away. By this time my near-panic had

turned from our slippery climb to the flash flood that might come sweeping down

the canyon at any minute if the rain continued.

But almost as soon as we reached the

jeep the torrent ceased, the roar of the water rapidly diminishing until only a

few small waterfalls could be heard. The

air regained its dry demeanor and the aroma of damp sage filled the

canyon. A few squawking ravens flew by,

their cries echoing off of moist sandstone.

I took my place behind the wheel and began driving the sandy road out of

Davis Canyon, commenting to Ken as we rumbled

homeward, “If every day here is as exciting as this one, I may not survive this

job!”

I was half-joking, soaked and

exhilarated, and breathless in a new realm.