It was over

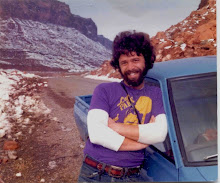

45 years ago that I blew into this bizarre and beautiful place to begin one of

the most extraordinary periods of my life.

I was young and fearless and full of energy when I started my tenure as

a park ranger in the Needles District of Canyonlands National Park. That was back in October of 1974. And now I am back again, under a tangle of

trees in campsite A7 in Squaw Flat.

Wooden Shoe Butte dominates the eastern landscape spreading its

tentacles of sandstone in all directions, into the drainages of Squaw Canyon

and Lost Canyon and the very edges of Salt Creek. The almost holy silence here is broken

occasionally by a squawking raven or a desperate visitor looking for a camp

site. I grabbed the very last one this

morning at 930am.

And that

was after a full bore drive down highway 211, passing cars at every opportunity

in hopes of finding a site. It helps to

have driven this road three or four hundred times over the years, knowing every

curve and canyon, recognizing individual cottonwood trees and petroglyph

panels. It begins at Church Rock

junction with a long open stretch through overgrazed grass and sagebrush, the

long climb to abandoned Ogden Center and through Photographers Gap, then down

toward the drainage from Harts Draw and the flanks of the Abajo Mountains. The section down the Dugway is steep and

curvy and used to be treacherous in the winter months. A few errant ponderosas have taken root in

the Navajo sandstone. Just beyond the

switchbacks Indian Creek flows in from the south to give the canyon its name

and character.

And that

was after a full bore drive down highway 211, passing cars at every opportunity

in hopes of finding a site. It helps to

have driven this road three or four hundred times over the years, knowing every

curve and canyon, recognizing individual cottonwood trees and petroglyph

panels. It begins at Church Rock

junction with a long open stretch through overgrazed grass and sagebrush, the

long climb to abandoned Ogden Center and through Photographers Gap, then down

toward the drainage from Harts Draw and the flanks of the Abajo Mountains. The section down the Dugway is steep and

curvy and used to be treacherous in the winter months. A few errant ponderosas have taken root in

the Navajo sandstone. Just beyond the

switchbacks Indian Creek flows in from the south to give the canyon its name

and character.

A thick

canopy of trees heralds Newspaper Rock and forms an arboreal tunnel for several

miles as the canyon walls stay close.

Here and there an etched big horn or shaman figure show themselves on a

sandstone wall. As the canyon widens,

the trees stay with the creek while the road meanders along the base of high

red cliffs. The sky opens up, the

sandstone pulls away, and the cattle appear around the grasslands near the

Dugout Ranch. The first signs of

historic humanity for several miles. I

could finally put the pedal to the metal on the Subaru and make like lightning

for the campground where I felt welcome and secure.

Little

Spring Canyon welcomed me back again as well after a hiatus of many years. My secret place, private getaway, and

pleasuring ground is harder for a 69 year old man to get into than a 29 year

old but I managed. I kept thinking that

this would probably be my last shot at it so I was determined to make it at

least as far as the first set of springs under the cottonwood gallery

downstream. Having a walking stick

really helped but I still stumbled and bumbled my way over the hard gray

limestone and the crumbling weathered sandstone shelves. I bouldered down a small pour off and

squeezed through a rocky tunnel before reaching the edges of the canyon where I

descended on an old deer trail to the sandy floor.

The

memories came flooding back even before I had reached level ground. I recognized an old juniper snag, little

changed in four decades. I remembered

the first time Susan and I discovered this place, in the dead of winter no

less. Frozen formations of ice along the banks portended bubbling pools in the

spring. And so it was. By mid May there was lots of cold, fresh

water seeping to the surface at the cottonwood gallery, then trickling on down

the canyon in a series of pools, cascades and freshets. Places to soak a naked body. Places to make love in utter privacy and openness.

There

was the time that Phil and I ingested some mescaline and spent a very long day

hiking downstream as far as we could, to the imposing confluence of Big Spring Canyon

and then to the even more imposing confluence

of Salt Creek. We traversed

ledges full of fossil crinoids and brachiopods.

We walked through dark polished halls of limestone. We thought we could walk all the way to the

Colorado River but we eventually got rimmed out. And then we hiked all the way back to the

front country. All in one unbelievable

day.

There

was the time Cindy and I got caught in a savage rainstorm near the confluence

of Big and Little Spring and hiked like hell to find shelter high above the

creek. I was expecting a flash flood

that never came, but we spent a primal night in a large alcove above the

springs, firelight flickering off of walls like a Pleistocene parlor.

One

summer Mary Ann and I discovered a cache of ancient puebloan artifacts near the

first spring. There were several

arrowheads, part of a woven yucca sandal, a ringlet of pressed desiccated

flowers, an arrow shaft. We stashed it

all back where it came from. I looked

for it today but there are only a few flaked lithics left at the site. For years we swore ourselves to secrecy that

we would never mention the name of the place.

But people are still getting down there even though the canyon is not

marked nor advertised.

Yet

today it did, indeed, seem to welcome me back.

The springs are not as vigorous as they used to be. Clean, fresh water no longer bubbles out of

the ground. Instead there is a much

smaller seep that feeds the creek with a shallow, algae lined run. Maybe the water table has dropped. Maybe too much water has been diverted over

the years to keep the thirsty campers happy.

Maybe as with me, age has taken a certain toll. In any case, the big cottonwoods

still hold sway. They were all shades of

gold and yellow today and huddled together thickly downstream, a riparian

fortress I could not break through.

But none

of that truly mattered. I had made it

back. And I made it back out as

well. And I am grateful to be among a

probable handful of people who have really experienced this place...and maybe

it has become a secret place for them as well.

If there ever was an Eden it must have been very much like this hidden

garden in the midst of a wilderness of stone.

I grow older and less able but the canyon remains and I know it is still there and still vital, and

that's good enough for me.